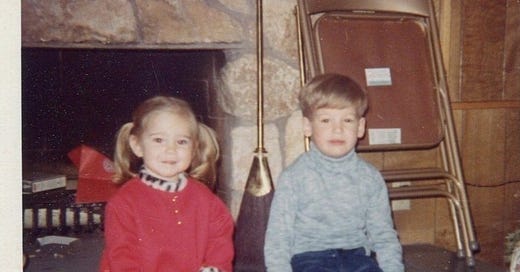

When I was five, I lived in an apartment complex in rural eastern Washington with my mother and big brother. Called the Green Trees, the name was misleading, unless the ones painted on the sign counted. My Palos Verdes princess canopy bed and dresser felt oversized in my new room, but then I jumped up and down on the mattress. Wild leaps, I grazed the wall, but then fell onto my bed, safe and sound. Yes, I decided, I could work with this.

My brother Garth's slightly bigger room was two doors down. Was it a perk of being three years my senior? My gut said, 'Yes!' Born with a mental measuring tape, I'm sure on move-in day, I pitched a fit. Then when November storms rolled through the Columbia Basin, I learned why the paint on his ceiling was riddled with rust-colored blotches. If the price for extra square footage was a leak and a drip bucket, he could have it.

Extra space wasn't the only privilege Garth's age afforded him. After school I went to daycare, while Garth ambled home to enjoy a few hours of true freedom. I imagined him eating bowl after bowl of cereal stretched out across the sofa and watching cartoons.

Daycare was run out of a single-family home a stone's throw from the Green Trees. I have no memory of what the house interior looked like because kids weren't allowed to linger there. A faceless adult zipped up my coat and pushed me out the back door.

Five steps down was the yard; a slab of concrete and a swatch of weedy grass speckled with a single cedar tree and a scrappy bush or two. We roamed the fence line like a pack of dogs, rattling the chain link and testing the footholds for a possible quick escape.

The lack of greenery in the yard made hide and seek pointless. Tag was out of the question, too. In fact, the single most popular activity was to stand on the slab of concrete and wait for our parents to show up. My hopes rose each time a flash of headlights flickered across the house. I gave the stink eye to every child that left before me.

Some kids were chosen to go inside the house to 'warm up,' with little explanation given to the rest of us.

I would find out in the weeks that followed, I was lucky.

On a few occasions, Garth showed up on the other side of the fence on his bike. The first time I spotted him, I assumed he'd come to rescue me. The scenario played out in my head like a Shirley Temple movie. Garth would express how much he missed me, that cartoons weren't as funny when he watched them alone, the cereal, too, wasn't as sweet. After wiping the tears from his freckled cheeks, he'd talk me through how best to climb the six-foot barrier and as I neared the top, he'd stretch out his arms to catch me. Oh, I'd been a fool.

He watched for me, pleased at the smile across my face as I came near. As I licked my lips, ready to wiggle the toe of my shoe into the chain link, he rode away, his laughter hanging in the air like a fart.

The routine changed when a provider at the daycare was accused of molesting children. I was pulled out immediately. It did not matter that my mother had no backup plan. My safety mattered most. Pragmatically, though, she needed time to find and vet a new care center or babysitter.

In the meantime, after class Mom picked me up and drove to the school where she taught. For whatever reason, she thought it would be wrong to have me join her students. Instead, I became an informal addition to Mike's afternoon kindergarten. I had no idea this man would become important to my family for decades to come. He would be my mother's partner for the next 50 years.

Mike would be the person Garth and I would dub, Super Mom.

Mike loved to tell me the story of when and how he first fell in love with my mom. They met during playground duty. For Mike, it was love at first sight. The picture of them standing on asphalt, both with their cool 70s locks, bellbottoms, faux fur coats, getting to know each other as they mitigated arguments over kickball cheats and jump rope injuries, makes me giddy.

My mother was fresh off the heels of an ugly divorce. This was an era when her leaving meant the good credit she had accrued in the marriage was given to him, leaving her as a credit risk when she'd kept the books all those years. Not only that, but she'd been tossed out of the catholic church she'd known her whole life, a place that swore they were a solid foundation until eternity, until they weren't. (Good riddance. They didn't deserve her.)

Like emotional boot camp, she had to learn how to be self-reliant overnight. And after the summer struggle session, the last thing she sought was a man.

Mike, though, was undeterred. He knew she was the one for him. They could be best friends until their dying days, and that would be enough. Hell! more than enough. He'd fallen in love and would settle for any relationship that my mother was comfortable having.

The difference between daycare and Mike's kindergarten classroom was like watching a grainy black and white television, then switching to color. Mr. Prudhomme, as he told us to call him, was funny, kind, and gave instructions in both English and Spanish. He was in a grown man's body, but had a childlike zest for fun like us! He seemed to feed off our sense of wonder and joy. An acoustic guitar was propped up in the same corner where the dunce stool sat in my morning class. He'd never resort to public shame to rein in his students. And that guitar guaranteed he had and kept our attention, not by threat, but out of curiosity.

My morning class, taught by Mrs. Hosack across the river in Richland, felt like a trip to the dentist, smelled like it, too. I didn't know it then, but Lewis and Clark Elementary was brand new. The walls were meticulous, chalkboards unmarred, carpets free of barf stains and paint spills, every lightbulb worked, and the desks matched.

On the first day of school, Mrs. Hosack introduced herself as a last-year-teacher, smirking as she shared that she would be retiring in June. That drew a raised eyebrow from my mother, who sat in the back with her mother, Grandma Snezeck, who did not want to miss my first day of elementary school. Dressed in spiffy plaid pants and a matching turtleneck, I was delighted to have an audience. Not one to disappoint, I was in top-form, raising my hand, answering questions, and then, well, I'm not sure what I did wrong.

I remember being grabbed by the arm and directed to a stool in the corner, a dunce hat plunked on my head. Mrs. Hosack had shown no consideration for my blonde, shiny ponytails. I'd only ever seen that conical shame-crown on Saturday morning cartoons. All I can guess is that I was too much for Mrs. Hosack, as was Amy Badbadda, who became my friend the instant she shared the stool and dunce hat with me.

My mother apologized to me after school let out, saying the dunce hat had been because of her. She'd had a word with Mrs. Hosack prior to the first bell, saying she, too, was a kindergarten teacher. It had been done in good faith, to foster kinship and maybe plant a seed of hope that I would merit a speck more attention than the other students. My mom felt it had done the opposite, made my teacher defensive and petulant.

I didn't care. I had a new friend and was soon to make a few more.

A week or so after being plucked out of daycare, my mother found a reliable family who could watch me after school. Their daughter, Karla, went to Lewis and Clark Elementary, too. She was one of the Hutton family, all five were pink-cheeked, shaped like shiny apples. Garth would go with me because they had a son his age. The Huttons let us inside their house. They taught me about VCRs and soap operas. On nights when my mother had late meetings, the Huttons shared their Weight Watchers salmon patties with us.

I missed the technicolor classroom across the Columbia, with the vibrant teacher at the helm. But I would see him again soon enough, and often.

Looking back, I believe that trusting Mike with me had done wonders to chip away the calcium wall around my mother's heart. Soon, she, Garth and I, dressed in our best party clothes, were invited to Guajardo's, the best restaurant in Pasco, where we had dinner with Mike.

I've only been told the following story. I do not recall the moment I climbed onto the table, coaxed by the sounds of canned mariachi music and twirled around and around, showing off my fluttery skirt. But, it happened.

The whole restaurant bore witness, everyone but Garth. He was busy choking on house made salsa, gulping down orange soda to extinguish the fire in his mouth.

Mortified, my mother coaxed me down, then dared to glance at Mike to apologize. I don't know what got into Jennifer. She's never done anything like this before (I had and would again.) Instead of judgment or derision, Mike's expression was rosy with love, for me, for Garth, and my mother. He'd fallen for the whole damn bunch of us.

Four years later, when we moved out of our apartment into a house in Pasco, my mother managed to lose my Precious Moments-praying-girl-lamp, given to me by Grandma and Grandpa Snezeck. But, I gained a Mike, and his fluffy white Samoyed, Sasha.

It was a trade to beat all trades.

Dear Jennifer, I’m not sure if we’ve ever met in person, but my husband, Lars, and I lived near your Dad and Stepmom in Fort Bragg. (Sorry for the multiply - complex sentence) I just want to let you know how very must I appreciate and enjoy your “scribbled thoughts”. Keep it up, girl! You’re good♥️ Kate Larson